Архитектура

- Все книги раздела

- Антологии

- Ежегодники

- Журналы

- Архитектурные конкурсы

- Архитектура Востока

- Архитектурные стили

- Атласы, энциклопедии, словари

- Высотные здания

- Города мира

- Дизайн жилых интерьеров

- Дизайн коммерческих интерьеров

- Дизайн офисов

- История архитектуры

- Кафе, бары, рестораны

- Конструкции и проектирование

- Ландшафтный дизайн, сады

- Магазины, витрины, стенды

- Материалы

- Многоквартирные дома

- Монографии. Сборники работ

- Общественные здания и пространства

- Отели и курорты

- Рисунок

- Страны мира

- Строительство, реконструкция

- Урбанизм

- Учебники. Справочники

- Философия архитектуры

- Частные дома

- Деревянные дома

- Эко архитектура

- Элементы

- Бассейны

- Камины, очаги, печи

- Колористика

- Текстиль, шторы, портьеры

- Разное

- Промышленные здания и постройки

Дизайн

- Все книги раздела

- Айдентика, логотипы

- Атласы, энциклопедии, словари

- Графический дизайн

- Дизайн в моде, фэшн дизайн

- Дизайн выставок и ивентов

- Дизайн в рекламе

- Дизайн вывесок, указателей

- Дизайн мебели

- Дизайн упаковки

- Ежегодники, Каталоги

- Журналы

- Интерактивный дизайн. Web-дизайн

- История дизайна

- Колористика

- Креатив

- Крой, вышивка, декорирование ткани

- Мир Востока

- Орнаменты

- Открытки, календари

- Печатные издания

- Постеры, иллюстрации

- Промышленный дизайн

- Рисунок

- Сборники работ

- Теория дизайна

- Типографика, Шрифты, Леттеринг

- Учебники

- Флористика, Entertaining

- Ювелирные украшения

- Разное

Искусство

- Все книги раздела

- Антиквариат

- Антологии

- Атласы, энциклопедии, словари

- Боди-арт

- Граффити, street art, urban art

- Живопись

- Малая серия книг по живописи

- История искусства

- Каталоги

- Кино

- Комиксы

- Коллекционирование

- Мир Востока

- Музеи мира

- Музыка

- Обучающие пособия

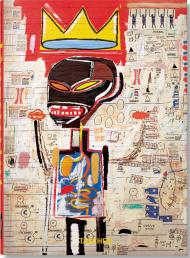

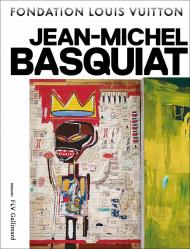

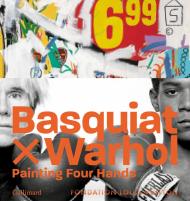

- Сборники работ

- Скульптура, Керамика

- Современное искусство

- Страны и культуры

- Теория искусства

- Ювелирные украшения

- Разное

Фото